VLADIMIR PUTIN is fighting a war he can’t win against forces he doesn’t understand.

That was the impression created by the Russian president’s own words — an unceasing torrent of them — when he was interviewed by Tucker Carlson last week.

The former Fox News host wanted to talk about the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and what actions Putin could take to end the war.

No one expected the Kremlin’s autocrat to call off the occupation or confess to war crimes on the spot.

But the way he evaded responsibility for the war he launched surprised even Carlson.

Putin retreated into history — all the way back to the year 862.

For 20 minutes he monologued about the evolution of Russia and Ukraine over a thousand years.

Carlson broke in, “I am not sure why it’s relevant to what happened two years ago.”

The lecture continued, so he tried again: If Russia’s grievances were so ancient, “why wouldn’t you just take (Ukraine) when you became president 24 years ago?”

When Putin still wouldn’t answer, Carlson asked once more, “why didn’t you make this case for the first 22 years as president, that Ukraine wasn’t a real country?”

Putin’s disquisition covered everything from Yaroslav the Wise and Genghis Khan to the early modern Polish-Lithuanian Republic to, eventually, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

As he closed in on the present, Putin had much to say about former Ukrainian leaders Leonid Kuchma and Viktor Yushchenko, as well as U.S. presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

Who was missing from the roll call of world-historic figures extending to the ninth century?

What contemporary leader seemingly played no role in shaping relations between Russia and Ukraine or Russia and NATO?

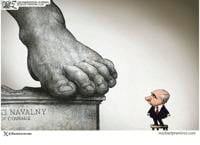

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin — the invisible man.

In Putin’s account, Russia hardly acts in history; rather it gets acted upon.

The most characteristic quality of Russia and its president, in his own telling, is passivity.

And why do other nations do the things they do to Russia, in his estimation?

Carlson told Putin “you’re clearly bitter” about NATO expansion and Western reluctance to make Russia a partner in European security after the Cold War — “But why do you think the West rebuffed you then? Why the hostility?”

Putin replied like a jilted teenager:

“No, it’s not bitterness, it’s just a statement of fact. ... We just realized we weren’t welcome there, that’s all. OK, fine.”

Nobody invites Russia to the prom.

Carlson gave him the only chance he’ll soon get to reach a mass American audience, but Putin’s message was pitched to Russia first, its region second, and lastly the non-Western world.

He wasn’t trying to move American opinion, not even to appeal to Trump Republicans or Tucker Carlson himself.

Indeed, Putin belittled and menaced his interviewer, following up a complaint about the CIA by calling it, “The organization you wanted to join back in the day, as I understand. Maybe we should thank God they didn’t let you in. Although, it is a serious organization.”

He made his opinion of Carlson clear from their first exchange, asking him, “Are we having a talk show or a serious conversation?”

When Carlson gave Putin an opening to discuss Russia’s Orthodox Christian civilization, Putin passed, emphasizing instead that “Russia has always been very loyal to those people who profess other religions” also, such as “Islam, Buddhism and Judaism.”

A multicultural moment from the Russian autocrat?

Putin chose not to frame his self-justifying narrative in terms that would play to America’s culture-war right.

He instead pitched his mythology to the anti-colonialist left, not only in the West but worldwide.

Putin imagines Russia a perpetual victim of privileged oppressors: “the golden billion.”

And he excuses his bloodshed by labeling it anti-fascist, an attempt at “de-Nazification” of a country with a Jewish president.

The point of his history tirade was to make Ukraine seem an imperialist creation — not only an illegitimate state but the spearhead of a thousand-year colonial project to subjugate ever-suffering Russia. This spiel finds few believers in the West, even on the “antifa” left.

The resentment Putin voices is meant for eager ears in China and the developing world, as well as Russia itself.

Who, however, really wants to join Russia on the losing side of a 1,200-year war?

Putin himself can hardly believe he’s going to win that war by brutalizing his neighbor.

But the whinging passivity of his portrait of Russian history, and the deletion of his own role in shaping events, isn’t just moral evasion; it’s a psychological prison.

Fatalism can be fascinating in a novelist or poet; in a dictator, it means war without aims or end.